Global Lens Reflections on life, the universe, and everything

No going back

Women in Nepal rely on education, faith, and credit to build better future

By Paul Jeffrey

Published in response magazine January 2024

Mamata Karki couldn’t find work in her home village in rural eastern Nepal, so she took her two daughters and moved to the capital city of Kathmandu.

“My husband didn’t want me to go, but there was no work for me there and no schools for the girls. I never went to school, and I wanted my girls to have an education. My husband wasn’t happy I’d given birth to girls instead of boys, and he didn’t think girls should be educated. So I took the girls and we came to the city,” she said.

They stayed with relatives at first while Karki worked in a brick factory. Her husband came after a few years, but his presence quickly became a problem.

“He was violent. He beat me. He was mad that I was earning money. He wanted me to stay home, but he didn’t have a job. Someone in the family needed to work,” she said.

In an attempt to appease her husband, Karki turned to tailoring, which allowed her to work from home. But her husband still wasn’t happy.

“To do the work I had to talk to my customers, but my husband didn’t like that I smiled at them,” she said. The beatings continued.

Karki decided she would lease a small plot of land and grow vegetables. She went to the office of Milijuli Samaj, a women’s organization recommended by a friend. Milijuli Samaj, which receives support from United Women in Faith, offered her seeds and training, and its staff visited her, providing encouragement and moral support. When Milijuli Samaj had workshops on raising cows and goats, she soaked up the information. She joined the organization’s savings and credit program, which provided financial support. Perhaps more importantly, other members provided a support group that convinced her to no longer tolerate violence. As a result, her husband finally left for good, and she filed for divorce.

Karki’s business grew. She sold at Kathmandu’s main vegetable market, but then buyers started coming to her small farm to buy at wholesale rates. With a loan from her savings group, she got cows and started selling milk. She wants to add a fish pond, as well as a fence that will allow her to raise chickens and goats. Digging a well is on her wish list.

Income from her farm has paid for her daughters to go to school. Pratima, the elder at 17, wants to become a bank manager.

“I’ve learned from my mother how to work hard. If you struggle as she has done, you can achieve a lot,” Pratima said.

Women lag behind

Discrimination against women and girls has a long history in Nepal, where a strongly patriarchal culture has meant lower levels of labor force participation for women, unequal pay compared to men, and high barriers for women to access education, health care, and credit.

When Nepal adopted a new Constitution in 2015, the document proclaimed the equality of all citizens and prohibited discrimination on the grounds of gender. In the same year, Nepal elected its first woman president, Bidhya Devi Bhandari. In 2016, Sushila Karki, an anti-corruption crusader, was elected as the first female chief justice of the Supreme Court. Although laws against child marriage, domestic violence, and dowry violence were also passed, they are widely ignored. And laws have not kept up with newer forms of gender-based violence such as online abuse. Despite progress in some areas, Nepal ranks 116th out of 146 countries in gender equality, according to the World Economic Forum’s 2023 Global Gender Gap Report.

Many forms of discrimination against women, including punishing lower caste women for the alleged practice of witchcraft, are closely tied to the complex combination of caste and class. In western Nepal especially, the practice of chhaupadi prohibits Hindu women from participating in normal family and social activities during menstruation, when they are kept out of the house and have to live in a shed. Although outlawed by the Supreme Court in 2005, the practice persists.

Parents play a key role in maintaining cultural forms of discrimination. Sati Shrestha, who manages the savings and credit cooperative of Milijuli Samaj, says gender bias begins early in life.

“Many girls are not in school, or they drop out after the 4th or 5th grade. Parents will push them to marry at an early age,” she said. “Many in our society don’t see a need for girls to go to school, or at least not to spend much on their education. If parents have a boy, they send him to a private boarding school while they send their girls to a government school. Why invest much in them if they’re soon going to marry and leave home?”

A large part of Milijuli Samaj’s work is focused on keeping girls in school, especially those being raised by single mothers. With funding from United Women in Faith, it gives scholarships that cover school tuition and fees, a uniform, school bag, books and notebooks for 30 girls a year. Milijuli Samaj staff visit the schools and talk to the students’ teachers. They bring the girls and their friends to workshops on a variety of themes from self-defense to keeping safe on the Internet. The girls’ mothers are invited to join the savings and credit cooperative and participate in workshops ranging from emotional self-resilience to pickle-making and worm composting.

Sangita Shrestha’s 12-year old daughter Deepshika receives one of the scholarships.

“She’s in 8th grade. She isn’t very good in sports but is excellent in academic things. She’s at the top of the class in test scores,” said her mother, who is a member of the Milijuli Samaj savings and credit program, and also enrolled in training to be a beautician.

Her daughter has set ambitious goals.

“I want to be a lawyer so I can fight corruption. That will help make Nepal a peaceful country,” Deepshika said.

The girl’s family was scraping together the funds to pay for her schooling, but then Deepshika’s father had to quit his job in an auto parts store to care for his father who developed cancer. When the older man died, Hindu tradition called for his son to wear white for a year in mourning. Hiring someone for a job during that period is considered a bad omen, so Deepshika’s father remains unemployed. Without the scholarship from Milijuli Samaj, Deepshika would have to drop out of school.

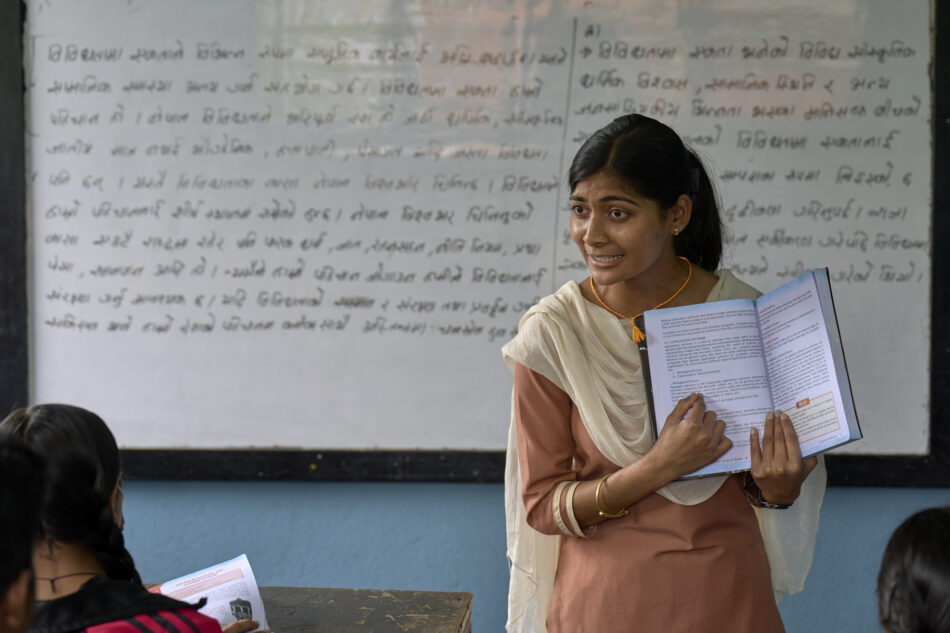

More than 400 women have received Milijuli Samaj scholarships in recent years. Urmila Bisswakaram is one of them. Now a teacher, she says she wouldn’t have made it without the help.

“I was the second of six children in our family. My father was a laborer and my mother was sick a lot. It was difficult to pay for both her medicines and our studies. If Milijuli Samaj hadn’t stepped in, I wouldn’t be where I am today. They really loved me and suffered for me. They encouraged me to never give up. Because of them, I can now do anything I want,” said Bisswakaram, who today covers the school fees of her younger siblings.

“Gives them power”

Providing scholarships doesn’t magically solve every problem young recipients face. Hira Nani Maharjan received a scholarship from Milijuli Samaj for eight years. An excellent student, she dreamed of becoming a teacher. But then the massive 2015 earthquake struck Nepal, and her family’s house tumbled to the ground. She was the only one in the family who could get a job, so she dropped out of school and went to work for a local private credit union, a job that allowed her to borrow the money necessary to rebuild the family’s home that she shares with her parents, grandmother, and two younger siblings. Eight years later, she’s still working for the credit union and repaying the loan.

“I move around and collect people’s contributions to their savings accounts. I visit 60 to 70 houses a day. It’s a good job, and people are happy to see me. But someday when the loan is paid off, I’d like to finish school and rekindle my goal of becoming a teacher,” she said.

Milijuli Samaj’s work of empowering women has a strong financial foundation. Women in self-help groups begin their journey together by joining the organization’s savings and credit program.

“Before, when a woman wanted to have money to buy something, she had to ask her husband for it. But when women have even a little bit of money of their own, they can do what they want with it. That gives them power,” said Sangita Karki, president of one Milijuli Samaj-backed savings group with 119 members.

Getting women started in that process, according to Diana Pradhan, a Milijuli Samaj director, is not necessarily complicated.

“Sometimes all we give a group getting started is one sewing machine and a few chairs, and they will find a space to gather and unload their problems on each other and together figure out how to solve them,” Pradhan said.

The solutions emerge from practical solidarity between women. In several Milijuli Samaj-backed groups, after listening to a woman share about experiencing domestic violence, the women have marched as a group to find the husband and let him know his violent behavior will no longer be tolerated.

“We believe that if we can give a little push to women, they will do well. We could talk all day about the challenges women face, but we’re done blaming the circumstances for our problems. We want to talk about women’s strength,” Pradhan said.

Once women have formed a group and all signed up for the savings and credit program, Milijuli Samaj offers a variety of workshops for them, ranging from emotional resilience to self-defense to nutrition. Using volunteer health care professionals, Milijuli Samaj conducts regular health checkups for women in the groups.

“Many women have long been confined in our homes, so we don’t go to the doctor. Maybe the men in the family won’t let us go, or there’s just no cultural understanding that we need to go unless we’re really sick. So problems like high blood sugar levels aren’t discovered until we hold our health camps, and then we get women into treatment. They won’t get treatment by themselves,” said Sangita Karki.

Livelihood training is a popular activity for the women’s groups. This includes making pickles, facemask lanyards, sanitary towels and soap, as well as training in baking, tailoring, and raising poultry and pigs. Workshops on growing mushrooms and making worm compost are well-attended.

If a woman starts a small business, she can ask her savings and credit group for a loan. According to Sangita Karki, women can borrow up to 50,000 Rupees (about $375). A committee of five group members reviews each loan, meeting with the applicant. Interest is 12 percent a year, but is waived for extremely poor members. Recipients have up to a year to repay, though if a woman has a hard time making her payments, the loan can be extended. Sangita Karki says no woman has ever defaulted on her loan.

By contrast, a bank loan is likely given at 17 percent or higher, but is more difficult to access.

“If you apply to a bank for a loan, you have to wait for a long time. And they don’t give small loans. They simply don’t see the poor as potential clients. And since many people in the Kathmandu Valley have migrated from the countryside, they don’t own land they can use as collateral, and thus don’t qualify,” said Sangita Karki.

“They want to use Facebook”

Just as Milijuli Samaj helps girls get an education, it also helps illiterate adult women learn to read and write.

“Most of our students grew up in remote mountain villages where there were no schools, or schools that girls weren’t allowed to attend. They came to the city to escape poverty, but an early marriage often prevented them from accessing educational opportunities,” said Sunita Nepal, a teacher in the adult literacy program at the Unnati Mahila School, where Milijuli Samaj–using funding from United Women in Faith–has provided notebooks for more than 50 new learners.

She says the women are highly motivated to learn.

“When they go to the market, they want to be able to understand the prices they see. When their relatives abroad contact them in WhatsApp, they want to be able to read that and reply. And they want to use Facebook,” she said.

Slowdowns during the Covid pandemic encouraged the expansion of digital literacy, as many businesses small and large had to find alternate ways to connect to their customers. Yet according to the World Bank, women across South Asia are 36 percent less likely to use the mobile internet than men.

Sunita Nepal says her students are eager to stop the digital divide from exacerbating the gender gap, but a variety of obstacles work against the women’s full participation. While some husbands, she says, are supportive of their wives becoming literate, others are opposed and won’t let their wives come to the school. Some women can’t afford the 100 Rupees tuition per month (about 75 cents). And others are pressured by their daughters or daughters-in-law to stay home to care for their grandchildren all day.

Yet for those who show up and put in the hard work, the reward is clear.

“After learning here, they are more independent. They no longer have to ask people to read things for them. They can do it themselves. They can chat and do video calls with their children working abroad. And they can count money properly and won’t allow anyone to cheat them. They are happy,” said Sunita Nepal.

“There’s no going back”

Meena Moktan is Nepalese, but grew up in India. She came home to Nepal 25 years ago at the age of 19, determined to share her Christian faith in a country that was once the world’s only Hindu monarchy. It wasn’t an easy task.

“I taught in a men’s Bible school, but outside the classroom I was allowed no formal role. A woman couldn’t enter the pulpit. But then in 2009 I joined The United Methodist Church, which gave me an opportunity to exercise my gifts of preaching and teaching,” Moktan said.

Besides becoming a leader in Hebron UMC in Kathmandu, Moktan was invited by Emma Cantor, the Manila-based regional missionary for United Women in Faith, to visit the Philippines and see for herself a variety of women in ministry.

“In the Philippines I got to know women leaders passionate about ministry,” she said, remembering when she spent time with the Rev. Leslie dela Cruz, who served a remote community of indigenous Aeta.

“She lived simply, and although she and her people didn’t have many physical resources to treasure, they were happy. I was inspired by both her passion for ministry and her freedom to exercise her gifts, giving her life to her people.”

Moktan came home from two trips to the Philippines determined to reach out in new ways to Nepalese women.

“There are women who are left out, who aren’t given opportunities, and I want to reach out to them to let them know they are special, to help them understand that although their society may not appreciate who they are, although they may think they are good for nothing, I want to raise them up with the love of God,” she said.

Moktan wanted to understand the obstacles that women faced in the church, a curiosity that she made the theme of a doctoral dissertation for a degree at a U.S. seminary.

She says education is a dividing factor, as boys are often sent to better private schools while girls are enrolled in crowded government schools or simply stay at home.

“Many compare this dynamic to watering a flower. Girls for them are like flowers, and you’ll waste water pouring it on them, investing in their education when they will eventually leave for someone else’s house, to be someone else’s wife. That perception keeps many parents from sending their girls for a good education,” Moktan said.

If a woman overcomes social pressure and achieves a leadership role in the church, she’s not home free. Moktan interviewed 22 women church leaders in Nepal for her research, and found many face a toxic work environment.

“One woman, an elder in her church, told me she wasn’t afraid of demons. She said she could cuss out the demons. She told me she was afraid of men,” Moktan said.

As a result, Moktan says women need a push.

“If they have no support, their talents are squeezed inside them. They need support. My husband encourages me, but other women have husbands who demand they stay home cooking food. Confidence and self-esteem are important, but you need affirmation to have confidence,” she said.

As part of that affirmation, Moktan and Cantor teamed up to lead an ecumenical workshop in May for women church leaders in the Kathmandu area. They spent three days looking at women leaders in the Bible and crafting strategies for how to help Nepalese church women find their place at the table.

Among the participants was the Rev. Manidevi Sunuwar, the priest of St. Petra Anglican Church, a congregation at the edge of a garbage dump in Kathmandu.

“In Nepali culture, priests are always male. When someone dies, the ceremony is done by a priest, who is always a man. When people see me, because of that cultural background, they ask how I can do what I do. How can I be both a woman and a priest?” she said. (There are female Hindu priests, but very few.)

Sunuwar says the workshop, including Cantor’s guidance in using Qigong, a series of Chinese exercises that aim to optimize energy within the body and spirit, helped her reflect on work-life balance and the need to care for her own spiritual needs while giving herself selflessly to others.

Sunuwar says listening to other women in the workshop helped her understand how far women in Nepal have come in such a short time.

“In the last few years, much has changed. Yet too much of that change is just on paper. In the next few years, we have to translate that paper change into real change,” Sunuwar said.

Samjhana Tamang is a member of Hebron UMC and participated in the workshop. She says women are called to be fearless.

“To be a woman in Nepal today means not being afraid. There’s no going back. We must serve God with all our heart and mind, and that means there’s no room for fear,” Tamang said.

In recent months Moktan has worked with the Rev. Jeewan Lama, the pastor of Hebron UMC, to lead workshops in rural areas of Nepal for churches from several denominations. She says the teamwork they model shows how traditional barriers to women’s full participation are falling.

“Women’s roles are growing. And not just because men are giving us opportunities. We are making our own opportunities,” Moktan said.

“Our country recently had a woman president for almost seven years. All around us, we can see women leaders doing good jobs. Nongovernmental organizations are mostly run by women. Social workers are mostly women. In both the society and the church, women are taking leadership roles. It’s a movement that can’t be stopped.”

The Rev. Paul Jeffrey is a photojournalist and senior correspondent for response. He lives in Oregon.