Global Lens Reflections on life, the universe, and everything

Sanctuary

A few days ago, Pope Francis paid an unannounced visit to a refugee center in Rome. He arrived without a motorcade and spent 90 minutes talking with refugees and the staff of the center, which is run by his order, the Jesuits. Afterwards, he urged the faithful to be better stewards of empty church buildings by using them to house those who flee hunger and violence in foreign lands. Focusing particularly on religious orders which, in the wake of declining vocations, have turned their convents and other buildings into trendy guest houses for tourists, Francis said, “The church does not need the empty convents to be turned into hotels to earn money. The empty houses are not ours. They are for the flesh of Christ, which are the refugees.”

When I read that story, I thought of Central Methodist Mission in Johannesburg, which I visited in 2009 to write a story about how the historic church in the middle of South Africa’s largest city had become a refuge for more than 3,000 people who had fled oppression and fear in neighboring Zimbabwe. Rather than finding welcome in South Africa, as one would expect considering the way South Africans were welcomed in Zimbabwe during the struggle against apartheid, many of the Zimbabweans instead found rejection and xenophobic violence. For many, especially the poorest, the only place they could find hospitality was the old Methodist church in downtown Joburg.

I spent a few days in Johannesburg, interviewing refugees in the church and some of the church staff, particularly Bishop Paul Verryn, whose commitment to the poor had forced open the doors of the church and kept them open, despite resistance from all sides, including from within the church. I wrote about the church’s ministry for both Response, the magazine of United Methodist Women, and the Christian Century.

It was a typical assignment: spend a few days someplace, fill my camera with images, my recorder with interviews, then come home and distill it down into two or three thousand words. It was a wonderfully complicated story, and thus a challenge to describe in so few words. (Yes, to me 2-3K words qualifies as “few words”–I’m not a good tweeter,) In the middle of such projects, I’m often jealous of those who have the opportunity to turn such slices of history into a book, exploring at length the political and personal roots of the conflict, teasing out the nuances, letting the characters fully develop.

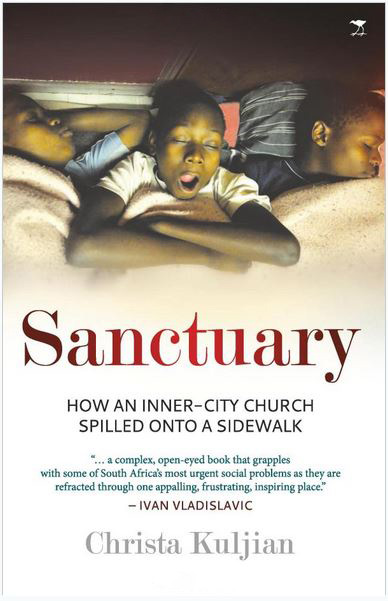

And now my jealousy has an target. Christa Kuljian, a freelance writer from Boston who lives in South Africa, has just published Sanctuary: How an inner-city church spilled onto a sidewalk. It’s the story of Central Methodist, but in telling that story in almost 400 pages, Kuljian takes us inside South African politics, both secular and ecclesiastical. It’s not always a pretty sight. Nor are there any clear heroes. Even Verryn, a fascinating guy whose stubborn commitment to the poor has pushed him into conflicts with everyone from Winnie Mandela to the Methodist Church’s top leaders, is described fairly, warts and all. The refugees in this book are real people as well, as Kuljian’s in-depth narratives reveal.

I was fascinated by Central’s history (and the excellent historical distinction between a First Methodist congregation and a Central Methodist congregation), which left it situated perfectly to respond to the growing influx of poor Zimbabweans. And yet its ministry didn’t emerge as the result of any long-term program planning; it was rather the openness of the church and its leaders to respond to the crises that developed around it. Rather than being seen as interruptions of the church’s life and ministry, they were seen as opportunities for courageous, faithful response.

If anything, the book’s faults center around its detailed nature. At times I got lost in the names and acronyms of anti-apartheid, church and government groups. But such is the risk of telling a story in depth. I recommend the book to anyone looking to think in new ways about mission and in fleshing out the Pope’s vision of using the physical resources of the church to meet the concrete needs of people who’ve been forced to flee their homes. This is a book for anyone who wants to understand how real people of faith take on real challenges, and then confront the resistance that inevitably comes from those made uncomfortable by the offer of hospitality to the poor.

Full disclosure: the book has a photo of mine on the cover. (But I’d recommend it even if it didn’t.) It’s an image of some boys sleeping inside Central Methodist. Three years ago I blogged about them, recalling the evening I photographed them as they lay down on the floor, covered up with blankets, and started to go to sleep in a room inside the church reserved for unaccompanied minor boys. We had talked for a while, me explaining to them why I was there and them telling me their stories of flight from Zimbabwe and what had happened to them since in Johannesburg. A few of them still weren’t sleepy, so we kept talking quietly. A couple of them wanted my email address (no matter how poor you are, you can have an email address). Then they announced that since I had interviewed them, they had the right to interview me. Ok, that’s fair. Their questions were precious, and I wrote some of them down in my notebook. Coming from some of the poorest people on earth, they are a primer on globalization.

Do you know Oprah?

Is it true you don’t have elephants in the United States?

Is wrestling real?

Have you met Tom Cruise? Mel Gibson? Brad Pitt? Etc.

Do you have dirt roads?

Do people in your country eat porridge like us?

Do kids there walk to school without shoes?

Can you walk five kilometers without shoes?

Do you have any wild animals there?

Are Indians red?

How much does a mountain bike cost?

I tried to turn the conversation back to their situation by describing the similarities of how we treat Mexican migrants in the U.S. That didn’t get us anywhere. One asked me, “How can you tell who is a Mexican?”

These boys are, as Francis reminded us, “the flesh of Christ.”

Links to more information about the book, including several reviews, can be found on its Facebook page.