Global Lens Reflections on life, the universe, and everything

A year in images – 2019

In her simple home in a Manila slum, 6-year old Clarisa Jugadora touches a photo of her grandparents, who were taken away by police during a assault on a poor community. Their bodies were found the next day. They were killed as part of the Philippines government’s so-called “war on drugs.” The girl believes her grandparents are in heaven, and every day when she comes home from school, she talks to their photograph, keeping them apprised of her life.

I met Clarisa early in 2019 during a visit to the Philippines to document how church activists are responding to the Duterte regime’s “war on drugs.” I wrote articles about this for both Catholic and United Methodist media. I told about how people like Norma Dollaga, a United Methodist deaconess, are working to comfort and encourage the survivors of what’s literally a war against the poor. Here’s Norma, on the right, walking with Clarisa’s mother, Kimberly, along the street where her parents were taken.

Here’s an image of Irma Locasia holding a photo of her son Salvador. He was killed in a police operation on this street on August 31, 2016, another victim of Duterte’s campaign. Irma is one of several relatives of people killed in the campaign who–with support from the deaconesses–have filed a case in the International Criminal Court, charging the Philippines president with crimes against humanity.

This campaign against violence and impunity has brought together both church activists and affected families. And the church response is broadly ecumenical. Besides Protestants like Norma and the other deaconesses, Catholics are also speaking out. In the Catholic article I linked to above, I quote Bishop Pablo Virgilio David of Kalookan. “There is no war against illegal drugs, because the supply is not being stopped. If they are really after illegal drugs, they would go after the big people, the manufacturers, the smugglers, the suppliers. But instead, they go after the victims of these people. So, I have come to the conclusion that this war on illegal drugs is illegal, immoral and anti-poor,” he said.

In an attempt to justify his policies by dehumanizing the victims, Duterte has claimed that drug users are the living dead. “I think he has been watching too many zombie movies,” Bishop David said when I asked him about this. “It is a kind of ‘othering,’ labeling them so that when they are found dead on the streets, people will be happy and respond, ‘Good, that’s one criminal less.'”

Another Catholic, Holy Spirit Sister Evelyn Jose, seen here in a Valentine’s Day demonstration against impunity, says Duterte’s war on drugs is a form of social cleansing. “The people being killed are the poor. They are drivers or scavengers, people who live in the slums, the poorest areas at the periphery of the city, and need to stay awake long hours. They think shabu helps them do that. They are addicts, not criminals. They are victims. They are sick people. And they are killed because some powerful people want to eliminate the poor,” she told me. “But for us in the church, for those who respect life, there is hope for these persons. If they can be given the proper assistance, if they are given a chance to be a new person, there’s hope. You can see that in the rehabilitation centers. Yet many have graduated and returned to their communities only to get killed because they are still on someone’s list. No allowance is made by the killers for someone who has been rehabilitated or healed. They don’t consider that. They just see them as a problem. They see them as an eyesore in society, people who don’t have a place. So they eliminate them.”

—–

I went to Okinawa early in the year to cover a seminar on women and militarization in Asia. Here’s an image of seminar participants exploring the Itokazu Abuchiragama cave. During intense fighting toward the end of World War II, the cave sheltered both Japanese soldiers and civilians. Many girls were forced to serve as nurses, often working in this and other caves where they cared for wounded soldiers. They were indoctrinated in the ideology of the Emperor, and the Japanese military instilled in them an intense fear of U.S. soldiers. The girls were convinced that Allied troops would rape them and turn them into comfort women (as the Japanese military had done to tens of thousands of women from China, Korea, and other countries it occupied). When it became clear that Japan was about to lose the bloody Battle of Okinawa, hundreds of the girls committed suicide, many jumping from cliffs into the sea.

The seminar was sponsored by United Methodist Women and the Wesley Center in Tokyo, and brought together women from throughout the region. Here are two participants, Mai Arino of Japan and Lina Yoon of South Korea, walking through a peace park in Itoman, Okinawa, where stone markers are inscribed with the names of more than 241,000 people who died in the Battle of Okinawa.

Here the participants gather to pray along the sea shore near a new U.S. Marine Corps airbase being constructed at Henoko.

In a February 2019 referendum, the people of Okinawa voted overwhelmingly against construction of the base, which is filling in a huge section of sea in order to build a new airfield. The referendum was part of a long struggle against the base, which includes people being arrested for attempting to block the entry of construction trucks into the new base.

Coordinating the seminar was the Rev. Hikari Chang, a regional missionary for United Methodist Women. Here she joins protesters blocking the gate of the new base.

—–

Back in the United States, I covered a specially called session of the United Methodist Church’s General Conference. Meeting in St. Louis, delegates considered several proposals about human sexuality, an issue which has divided the denomination in recent decades. This time around, conservatives pulled out all the stops in their quest to drive queers and their allies into either silence or exile. Their principle target is Karen Oliveto, a wonderful UM bishop who happens to be a lesbian. Here she is rallying the faithful in their failed effort to keep the church a place of inclusive grace.

I’m not a big fan of covering meetings, even huge ones, so I usually just say no to such opportunities. Among other reasons, it’s hard to make interesting photos of meetings. But this particular gathering gives me a chance to see good friends and to work beside some very competent colleagues who help me learn new skills.

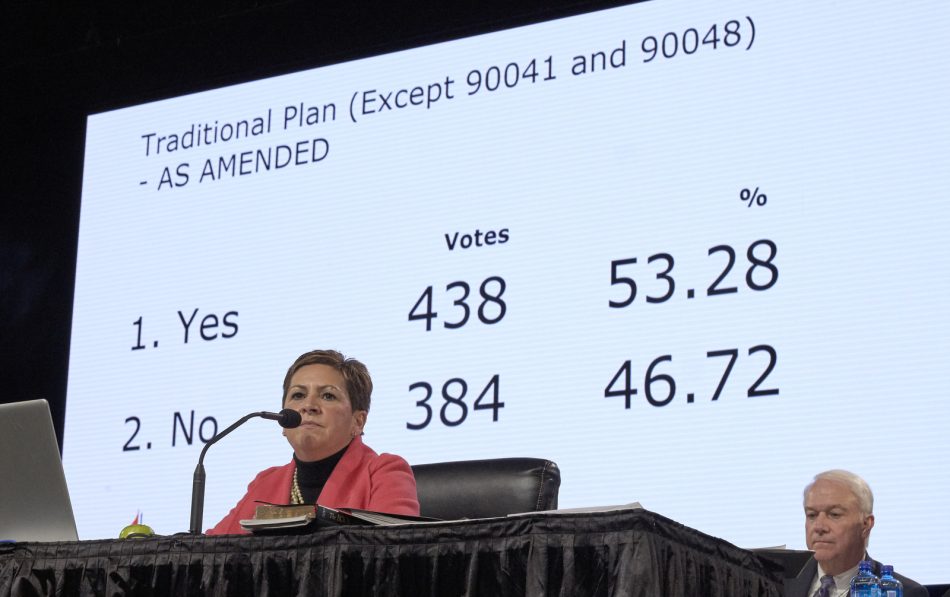

Whether they are visually interesting or not, there are some classic images of these conferences that reflect the actions taken, such as the announcement of voting results, and thus form part of the historical record. This photo of mine, for example, was used widely in the media. It’s not technically difficult. It just needs a high f/stop to keep everything in focus, some anticipation, and proper alignment (keeping the presiding bishop out of the way of the numbers while keeping the microphone out of the way of most of her face).

Fortunately, from my jaded perspective as a photographer, more dynamic action did break out occasionally. Following a key vote that approved the Traditional Plan, a draconian attempt by conservatives to take control of the denomination, demonstrators tried to disrupt the proceedings. Here’s an image of police preventing the Rev. Elizabeth Tay McVicker from entering the conference floor.

—–

Back on the road overseas, I made two trips to India to work on a long article for the March 2020 issue of response, the magazine of United Methodist Women. This coming year marks 150 years since the first two women missionaries were sent abroad by Methodist women, who had been forced to form their own mission agency. One of those pioneers was Isabella Thoburn, who shortly after she arrived in India in 1870 opened a simple classroom for six girls in a mud-walled room off the market in Lucknow. She had to post a guard at the door with a big club, because local Hindu priests had opposed the establishment of a school for girls. Thoburn nevertheless persisted, and that little school grew. After her death it was renamed Isabella Thoburn College, and for decades has been one of the premier institutes of higher education for young women in India. I got to hang out there for a few days, documenting life in the school.

Part of the mission of the school is to flesh out Isabella Thoburn’s motto, “We receive to give,” so students take regular trips to rural villages and urban slums. Ostensibly the trips allow the students to educate people about everything from HIV to dowry violence, but the underlying motivation is to expose girls from relatively wealthy families to life on the other side of the social chasm that bifurcates modern India. At a minimum it encourages some sense of noblesse oblige, but at best it helps graduate committed women determined to fight the double whammy of caste and creed that plagues India still. Here are some Isabella Thoburn students putting on an educational play in an urban squatter settlement.

I also visited Isabella Thoburn College in 2004. During both visits I accompanied a group of students for a trip to the countryside. And I couldn’t help but notice the impact technology has had. Fifteen years ago, the students walked around the village talking with people, as this young woman is doing, using a puppet to broach messages about HIV and AIDS.

This time around, the students seemed much more reticent to engage with the villagers, and spent an inordinate amount of time taking selfies of themselves. It’s well-known that I detest selfies, and watching how technology got in the way of human interaction here only reinforced my curmudgeonly attitude. I broached the problem with the school’s principal and president, and they sighed, telling me the steps they’d taken to mitigate the worst of mobile phone culture, but they felt like they were fighting a losing battle.

—–

Elsewhere in India, I spent a day at the Opportunity School in Chennai. It’s a wonderful center for children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Here’s a father dropping off his daughter at the beginning of a school day.

The school is run by Methodist deaconesses, including Kasthuri Devaraj, an 83-year old icon of the deaconess movement in India–another legacy of Isabella Thoburn. I was impressed with how they treat the kids with respect and creativity, despite a severe lack of resources.

Devaraj recently went on a fundraising trip to the U.S., but it wasn’t to help fund the daily activities of the school. Instead, it was to deal with effects of the climate crisis. Rising sea levels (a result of melting polar regions), coupled with Chennai slowly sinking (the result of poor urban planning that restricts replenishing the subterranean aquifer underneath the sprawling city), means that the ground floor of the school gets regularly flooded for weeks during typhoon season. The solution? Jack up the building and construct a taller foundation under it. The climate crisis means diverting scarce funds from mission to maintenance.

—–

I spent time with other Methodist deaconesses, including Omega Chandrashaker, here talking with students at the Mary Knotts Girls High School in Vikarabad, where she is an educator and hostel superintendent, and Laveena Anil, here singing with children as she helps them study after school in Moinabad, where she runs the Methodist student hostel.

And here’s Malathi Jamesraj, who helps poor women learn sewing and tailoring in Chennai. By increasing their earning capacity, she helps them earn money for family needs while at the same time gaining respect in their home and neighborhood.

As I followed deaconesses in their work in several areas around the country, I was impressed with their commitment and creativity, as well as their “Nevertheless, she persisted” attitude in the middle of a church that, to be honest, doesn’t prioritize deaconess work very much, and certainly doesn’t make available adequate resources to support their work or pay them decent salaries. The situation has been made worse by increased government intervention in rural education. That’s generally a good development, but it was a field the deaconesses had to themselves in some areas. At the same time, the government has made it more difficult for churches and NGOs to receive money from abroad. As a result, the funding of church schools is now more complicated, which makes many in the ruling Hindu nationalist BJP party quite happy. When I visited, many deaconesses hadn’t been paid in months, yet they remained committed to carrying forward the legacy of Isabella Thoburn, whether it’s with poor women learning tailoring in Chennai, school children in Moinabad, or women exploring spirituality in Hyderabad.

—–

During my visit to Hyderabad, I spent a couple of days in a retreat with Methodist women wondering together how they can better respond to the challenges of their faith within the context of a church that pays lip service to women’s importance within the faith community, but at the end of the day leaves decisions and resources in the hands of men. The gathering was facilitated by my friend Emma Cantor, an amazing Filipina deaconess who (like Hikari Chang above) serves as a regional missionary in Asia for United Methodist Women.

—–

During the summer, I captured a few photos of life in my backyard in Oregon.

—–

In preparation for the Vatican’s Synod on the Amazon in October, I spent several weeks in the Amazon region, accompanying Barbara Fraser, a Peru-based journalist, preparing material for Catholic News Service that was used widely before and during the Synod. While Barbara wrote the lyrics, I took advantage of the rich beauty of the Amazon, like this woman and child in Islandia, Peru, to compose the visual soundtrack.

Our itinerary included Colombia, Peru, Brazil and Guyana, and of all the places we visited, one photo that in some ways sums up what’s happening throughout the region is this one of indigenous children playing in an inflatable pool in a housing project for displaced families in Altamira, Brazil. Their families were displaced by the construction of the Belo Monte Dam from their villages along the Xingu River. As many as 40,000 people were displaced by the construction of the dam and flooding of the river, including these kids who once swam in the waters around their villages, but “progress” has upgraded their play to a cheap plastic pool.

Among the new friends I made on the trip was Luana Kanamari Bakero, here holding her doll in Atalaia do Norte, Brazil. The Kanamari indigenous girl painted the doll with her own tribe’s facial markings. She and her mother had come to visit Atalaia do Norte from their village several days upriver in a protected indigenous reserve. While in Atalaia do Norte, I also photographed people protesting a central government plan to turn control of health care over to municipalities, in effect destroying a federal program of indigenous health care. They’re worried that the government of President Jair Bolsonaro is reducing or eliminating protections for the country’s indigenous people.

—–

One of the issues we focused on was the migration of indigenous families from the deteriorating forests to crowded urban centers (see here and here). So I got to meet people like Samuel Alves da Silva, a 3-year old who is here posing as the Incredible Hulk in the one-room apartment he shares with his mother, Maria Ioni Brandowauvis, in Manaus, Brazil. The indigenous family migrated to the city in 2018, joining with other poor families to take over an unoccupied building in the city center.

Our desire to understand what happens to indigenous culture in that migration also led us to meet Ovidio Barreto, a Tukano indigenous healer, here blowing smoke on Humberto Peixoto, a Tuyuka Indian, during a treatment in the Bahse Rikowi Center for Indigenous Medicine in Manaus.

—–

Although stretched thin throughout the Amazon (one of the facts that led Francis to call the Synod), the church in many places has found its calling to defend the life of the people and the forest where they live. We spent some time in the state of Para, where Dorothy Stang, a Norte Dame de Namur sister from the U.S., was martyred in 2005. After an earlier visit, I wrote about Dorothy’s struggle to stop the steady deforestation of the Amazon.

Here’s Antonia Silva Lima, a farmer who worked closely with Dorothy, praying this year beside Dorothy’s grave outside Anapu, Brazil. The red cross bears the names of 16 local rights activists who have been murdered since Stang’s killing. Church activists say the killings continue, and they’re about to erect a second red cross with even more names.

Father José Amaro Lopes de Souza here poses for a photo in the room where he lives under house arrest in the local bishop’s residence in Altamira. He was the priest serving the Anapu parish and was a close friend and collaborator with Dorothy. An ardent human rights advocate, Amaro has pissed off the same people responsible for killing Dorothy. They evidently decided that having him killed would be too much, so they had him arrested in 2018 on what his defenders claim are invented charges.

—–

As Barbara and I wandered around the Amazon, besides courage and commitment, we also found tremendous beauty, whether in a fisher’s catch in Santarem, Brazil, or in the attempt of children to take flight during school recess in Hiowa, Guyana.

—–

We took a portion of the journey to focus on the response in Brazil to the arrival of huge numbers of Venezuelan refugees. I met people like Leonardo Cantillo, who with his son Fabian is seen here erecting a shelter at Tarau-Paru, a Pemon indigenous village just inside Brazil. Cantillo and his family fled Venezuela early in 2019 after new outbreaks of violence between the Venezuelan military and Pemon villagers. And in the nearby city of Boa Vista, here’s a Venezuelan refugee family sitting on a curb eating breakfast provided by some Catholic sisters.

—–

Wherever we went in the Amazon, we depended highly on the hospitality and insight of people like Consolata Sister Inés Arciniegas, seen here visiting with Venezuelan refugees who sleep in tents outside the main bus terminal in Boa Vista. The selfless commitment of Inés, who is from Colombia, left me humbled and hopeful about the future of the church in the region. Despite incurring the wrath of Brazil’s rapacious elites, servant leaders like Inés — and Dorothy and Amaro — provide a model for a church that truly accompanies the poor and marginalized.

—–

I also captured some video on the Amazon trip, and here’s a short piece mixing video and stills together into a short promo for the series of articles we produced.

—–

My next trip abroad was to the eastern portion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where I covered Ebola in Goma and Beni for IMA World Health. I confess I find the public health crisis engendered by Ebola to be fascinating. On one level, it’s just a virus. Although particularly virulent, it’s still just a small critter that wants to kill you. I can handle that. But it’s the context that makes Ebola especially dangerous. People in that part of the DRC have lived through incredible violence. What’s known as Africa’s World War killed some 6 million of them. The DRC is the rape capital of the world. Malaria kills people in droves. And basically the world doesn’t care. But when Ebola breaks out, foreigners in hazmat suits come running. And start bossing people around, telling them, for example, that they’ve got to change how they grieve over dead loved ones. That often doesn’t go over very well, and the resentment that results has led to attacks on health workers and clinics, weakening the Ebola response.

Nonetheless, what I personally experienced of that response was a robust screening everywhere I went. Many times a day someone was poking an infrared thermometer at my head and making me wash my hands in a diluted bleach solution.

—–

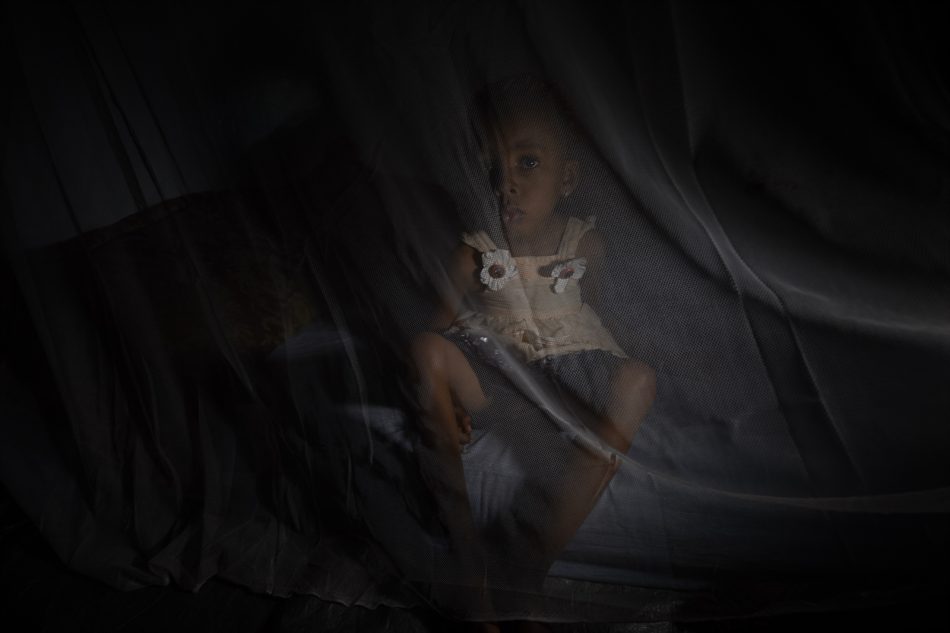

Part of what I wanted to do was put a new face on Ebola. And I found it in Christivie Mulonda, a 5-year old survivor of Ebola. Here she is sitting in the doorway of her family’s home in Beni, a city that became ground zero of the epidemic, which this time around broke out in 2018. Some of her family weren’t as fortunate, and the virus left her an orphan.

In large part she survived because of intervention by community health promoters tracing the contacts of people who been diagnosed with the disease. Although a vaccine was developed this year, it’s the software of the Ebola response–like the slow, patient labor of contact tracing–that saves lives at the end of the day. Following Christivie is Katembo Mastaki Barnabas. He also contracted Ebola, apparently while attending a funeral for someone who died of Ebola, but the contact tracers found him and he began treatment in a timely manner.

Besides the survivors, I also documented the work of the heroes. People like these two community health workers from the Programme de Promotion de Soins Santé Primaires, a faith-based NGO in Beni. Besides contact tracing, they also educate families in appropriate hygiene measures, like frequent hand washing with a diluted bleach solution. And then there’s an image of Adele Kavira Saasita, a nurse putting on her protective clothing in a clinic in Beni.

—–

Although documenting the Ebola response was my main focus, I also covered anti-malaria work, including the program that got an insecticide-treated bed net into Dayana Makazi’s home in Goma. The DRC is the second-leading country in the world for malaria cases. An outbreak of Ebola in the region in 2018 was accompanied by a huge spike in malaria cases. The two diseases often present similar symptoms in their early stages, making both more difficult to diagnose and treat.

—–

I also did some video interviews with women who are survivors of sexual and gender-based violence. Chamsi Djuma (left) is one of those women. Here’s she’s learning to read and write with help from her tutor, Katungu Sivayirwandeke Darlose. It’s part of a basic literacy program run by the Tushinde Ujeuri Project, which offers survivors of sexual and gender-based violence a new start on life, including helping become literate.

—–

As the year ends, I’m preparing to have hip surgery that will keep me at home for a couple of months. I’m also preparing for the February launch of a new photo agency–called Life on Earth Pictures–that I’m forming with colleagues from the U.K. and Sweden. More on that in the near future. Then later in the year, I’ll be taking my aftermarket hip on an introductory trip to several foreign destinations.

I remain enchanted with the work I am blessed with, and I give thanks for the privilege of entering people’s lives for a few moments or days and documenting their joys and struggles. I give thanks for them, ordinary people from the Amazon to India, from the Philippines to the Congo, who have offered me hospitality along the way.

Whether it’s a community along the Amazon or a Manila slum or Congolese village, I’m reminded during this Advent season that Jesus was born into just such a setting. As Thomas Merton wrote in Raids on the Unspeakable, “Into this world, this demented inn, in which there is absolutely no room for him at all, Christ has come uninvited. But because he cannot be at home in it, because he is out of place in it, and yet he must be in it, his place is with those others who do not belong, who are rejected by power, because they are regarded as weak, those who are discredited, who are denied the status of persons, tortured, exterminated. With those for whom there is no room, Christ is present in this world.”

Those words take flesh today in so many places around the world, including among the Warao indigenous refugees who have fled Venezuela for Brazil. Here’s a Warao mother and child in Boa Vista. They live in a park that they and other Warao refugee families invaded. They had previously been sheltered in a government refuge, but found the military-controlled environment oppressive. So they moved out and set up their own refuge in the park, where they receive some support from local residents.

May this coming year be a time for us to practice better hospitality, opening our homes and lives to those born and living in exile and at the margins of our community, those for whom there is no room.

The image used for this post on the home page of my blog is of a girl playing after school in Moinabad, India, where she stays in the Methodist student hostel.

One Response to A year in images – 2019