Global Lens Reflections on life, the universe, and everything

Southern Sudan: Advent waiting

It’s the first Sunday of Advent, and I’m somewhere over the west coast of Africa, sitting in a cramped economy class seat on a 17-hour flight from Johannesburg to Washington. I’m trying to get into the zen of waiting, if for no other reason than I have no choice but to just sit here. And wait.

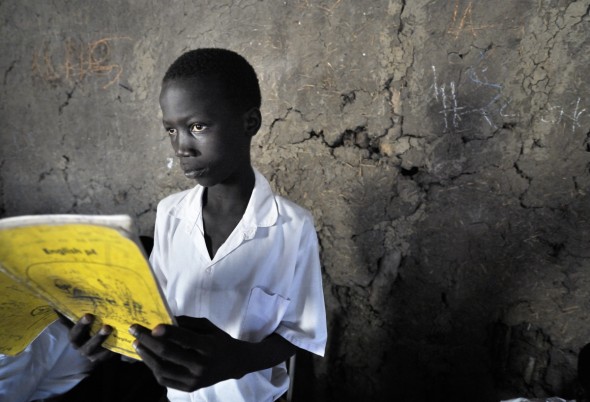

The people of Southern Sudan, where I just spent the last two weeks, have been waiting a long time to be free. They’ll have a chance at freedom, unless something goes wrong at the last minute, when in January they vote on a referendum on secession from the north of the country. All of their recent history–from being sold out by the British when the empire pulled out of Sudan, through two long civil wars with the north, through the long death marches of the Lost Boys and Lost Girls, through the decades of the world not caring about slavery or aerial bombing, through the agonizing years of negotiations to bring about the 2005 cease fire, to the contradictions and birth pangs of creating a new nation out of a contentious amalgamation of ethnic groups and competing militias–will come to fruition as they cast their ballots for separation from the oppressive north. Make no mistake, they will vote overwhelmingly for independence; this will be one of those rare elections when a 90+ percent approval really means that. The real question is whether the north will respect the will of the people of the south. If Khartoum does let them go, then the real hard work will begin of crafting a national infrastructure which will guarantee both economic development and individual freedom. For now, in the days leading up to the vote, there’s a heady enthusiasm about what many there view as a fulcrum point of history.

I was invited to come on this trip by folks from Solidarity with Southern Sudan, a coalition of dozens of Catholic religious orders that sponsors some two dozen educational, health and pastoral workers from different orders in four communities in the nascent country. Solidarity is a fascinating experiment in mission, as it breaks the traditional model of each order doing its own thing. We Protestants would call it ecumenical, and it is that, indeed; they even welcomed a wayward Methodist into their midst. They even welcomed me as a journalist, knowing that the story of Southern Sudan has not been told well or widely. (One exception: Sister Cathy Arata was somewhat reluctant to be interviewed. She’s a wise nun from New Jersey who worked in El Salvador for many years and is now in Juba. In May, the New York Times’ Nicholas Kristof wrote a column in which he contrasts “the old boys’ club of the Vatican and the grass-roots network of humble priests, nuns and laity in places like Sudan.” Cathy had let Kristof interview her, and he repaid the favor by nominating her to be pope, something that Cathy, the epitome of humility, found highly embarrassing. To get her to talk with me, I had to promise not to praise her. So I won’t. But if I were a Roman Catholic, I would second Kristof’s motion.)

Given its rapid transformation over just a handful of years from a ravaged battleground into a modern state in the making, Southern Sudan has attracted a plethora of non-governmental organizations. There’s an NGO on every corner and for every cause. Many of them are doing good work. But there’s also something intrinsically distinct from the work they do and the work of the church, as embodied both by the Southern Sudanese church, which never ran away when the wars turned incredibly brutal, and by the foreign missionaries who also stayed with the people through thick and thin. Many of the NGOs in Sudan sent their expat staff out of the country earlier this year because they were afraid of violence during national elections; some of them are planning similar evacuations around the referendum. Not so the church. As one man who lives along the contentious and ill-defined border-to-be with the north of the country said to me: “When the NGOs come here, they have an exit strategy. When the church comes, we know it comes to stay.”

In Malakal, I met Father Peter Major, a Mill Hill missionary from upstate New York who has spent decades in East Africa, accompanying the people, whether they were living under enemy bombs or in refugee camps in Kenya. He’s been held hostage, sentenced to death, and in the process developed a delightful sense of humor like none I’ve encountered in quite some time. His sense of peaceful permanence was inspiring, and a dramatic contrast to the NGO culture with their endless security briefings and protocols. Don’t get me wrong, I like staying alive and am glad there are people who focus on clarifying the objective danger that often accompanies humanitarian work. But if Jesus had had a security officer in his entourage, the incarnation would have taken different form. That’s why groups like the Christian Peacemaker Teams offer a valuable opportunity for mission-minded people to engage the world today. We need less people going to build cement block churches on Volunteer in Mission teams, which can contribute to a culture of dependency and actually reinforce unjust power relationships (thus not changing anything in the long run), and more good church folks joining groups like CPT, Peace Brigades International and the Ecumenical Accompaniment Program in Palestine and Israel.

A few months ago I discovered a wonderful book about some missionaries in South Korea in the 1970s who because of their commitment to accompanying the people got caught up in the struggle for democracy. More than Witnesses: How a small group of missionaries aided Korea’s democratic revolution is a collection of writings by several of them, and I found one passage from fellow United Methodist Missionary Gene Matthews to be specially profound. He had related how their little group of US missionaries had befriended the wives of eight Korean men arrested on false charges of treason. The missionaries were there at the prison gates, accompanying the women, when they learn that all the men have been executed.

Father Sinnott and I, along with Willa Kernen and a couple of missionaries from the Maryknoll Sisters, set up shop in front of the gate. We had become very close to these women during the past year as we joined in the struggle to proclaim the innocence of their husbands. We had cried with them numerous times and even laughed with them during unexpected moments of amusement. During that time we never ceased to hope that the end of their story would be a joyful one. Now they had been brought to a state of ultimate hopelessness and despair.

Eventually the wives began coming out of the prison yard one by one, most of them in near-total states of shock. As they came through the gate, they collapsed into our arms. We comforted them; we cried with them; we propped them up as they vented their anger at the world. We embraced them as they cursed the president, the riot police who sat in their bus taunting them, and in one case cursed even God. We felt totally helpless.

At one point, Father Sinnott forced his way through the gate and stood inside “preaching” to the guards. A plainclothesman arrived and pled with me to talk him into leaving. I refused and they finally carried him out bodily.

The events of that day seem almost frozen in time. As I reflect on them, I often think of them in the context of all the words produced by the established church. I have nothing against such words, and I have produced a substantial quantity of them myself. But suddenly I was in the middle of a situation where the church which I represented had no words. There was nothing we could possibly have said to those women at that time that would have made any sense to them. So we took them in our arms and cried with them. It occurs to me that the church would do well to find itself from time to time in situations like that – where all it can do in the name of Jesus Christ is cry, because injustice has burned a hole in its heart.

As I sit here waiting for this endless flight to get somewhere, people all over the world are waiting for food and water and dignity. As we wrestle with how to accompany them, let’s keep the UN agencies and NGOs in business. They are the modern, secular expression of what was long the purview of faith communities: health care, water, education, shelter, community organization for people displaced by war or nature. Essential, holy work. But people don’t wait for bread alone, and they don’t only wait in safe environments. They need the Word made flesh, and we who struggle to make mission real and concrete must overcome our at times myopic concern for security and focus more on how we can simply accompany God’s people in authentic ways. As Dan Berrigan once said, “Don’t just do something, stand there.”

Advent is a time of waiting for God to come to accompany us. May this Advent be an opportunity for us to tune our sense of waiting, and, as we wait, to reflect on how we can better accompany those who wait for God to “disperse the gloomy clouds of night, and death’s dark shadows put to flight.”

Happy advent.

6 Responses to Southern Sudan: Advent waiting