Global Lens Reflections on life, the universe, and everything

A Year in Pictures – 2021

When I got my first coronavirus vaccine shot almost a year ago, I had high hopes that 2021 would prove different than its predecessor. I started to make plans for trips abroad. And then came shot number two, and I felt ready to take on the world. Sadly, the world wasn’t as fortunate as me. Places I needed to go, like the Philippines and Indonesia, tightened restrictions on foreigners as Covid ran amuck. That meant more months of staying home. Which meant more months of capturing images of my big Pacific Northwest backyard. Like a Western trillium (Trillium ovatum) in the deep woods. Or the ubiquitous rhododendron photographed before dawn.

Where you have flowers, you have bugs, like this Western tiger swallowtail (Papilio rutulus) slurping nectar from a native Mock orange (Philadelphus lewisii) in my garden, its legs covered with pollen. Since their lifespan as a butterfly is only two weeks or less, there’s no time to waste, so they’re great bugs to watch. Despite significant habitat depletion, Swallowtails remain pretty common in western North America. Unlike the endangered Monarch, which has evolved to depend on milkweed, the Swallowtails aren’t as picky about food sources and where they lay their eggs. So they fare much better. Their larvae are a favorite food of birds, but particularly in caterpillar form they’ve developed a pretty cool chemical defense, converting aristolochic acids found in their host plants into a spray that when frightened they squirt out of a forked organ called an osmeterium. That was my Scrabble word for 2021.

And where you have bugs, you’ll have birds, whether it’s a Red-winged blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) catching a morsel in midair or a tiny Bushtit (Psaltriparus minimus) eyeing tasty honeysuckle aphids (Hyadaphis passerinii) while hanging upside down on native honeysuckle (Lonicera ciliosa). Or a Spotted towhee (Pipilo maculatus) chowing down on a yellowjacket (Vespula spp).

Most days I didn’t have to go far to find birds to photograph. On a branch outside my bedroom window I watched Cedar waxwings (Bombycilla cedrorum) engage in courting behavior by passing food back and forth.

Sometimes it would get complicated. One day in May, a whole museum of waxwings showed up, with several pairs of birds sharing berries. And then there were these three birds. The one in the middle kept sharing its fruit first with one, then with the other, hopping back and forth along the osoberry branch. Cue the Luvin’ Spoonful singing “Did You Ever Have to Make Up Your Mind?”

The pond in our backyard is a magnet for many types of birds, including this Green heron (Butorides virescens). It’s one of the world’s few tool-using bird species, often creating fishing lures with insects and feathers, dropping them on the water to entice small fish to the surface where it grabs them. And we had Hooded mergansers (Lophodytes cucullatus) show up early in the year, including this male who put on an impressive mating ritual where it throws its head back and makes sexy noises.

Having ducks on the pond also meant having hungry big birds around. Hawks and owls and other raptors were frequent visitors. We saw that when some baby mallards appeared in the spring time. At first there were eleven. Then hawks would show up, sending the ducks and crows into a tizzy. (When I hear the crows frantically cawing, I run outside to look for hawks.) Then there were nine ducklings. Then five. Then three. Then one. Finally, they were all gone. Nature can be cruel, especially when we arbitrarily assign “cuteness” to some species but not to others.

A similar dynamic took place when we discovered a Bushtit nest in our backyard. The little birds (each weighs about the same as three paperclips) built it as a community, as unattached males voluntarily chip in their labor. I started shooting video of them flying in and out of the hanging nest with bits of feather and moss, wiggling around inside as they got it ready. I wanted to document their life all the way to the babies emerging. We were worried about squirrels getting to it, so sprayed a hot pepper mixture on the branches nearby, which prevented squirrels from getting to the nest. But one day, we think just before the babies hatched, we found the nest with a big hole in its side, the Bushtits gone. It was probably a hungry crow or hawk. Fortunately, we still have Bushtits in our little patch of creation.

Even smaller than the Bushtit are hummingbirds, and we’re blessed to have their almost constant accompaniment. Here’s a female Anna’s hummingbird (Calypte anna) enjoying the Red flowering currant (Ribes sanguineum) in our garden.

Beyond our garden and pond, we are fortunate to live in a region blessed by wonderful birds, from the tiny yet raucous Marsh wren (Cistothorus palustris), the fascinating amphibious Water ouzel (Cinclus mexicanus), to hungry giant Ospreys (Pandion haliaetus), a Northern harrier (Circus hudsonius) carrying its dinner, and magnificent Bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), to a googly-eyed male American bittern (Botaurus lentiginosus) with its unforgettable thumping mating call.

This past year I acquired a drone. I took the examination and was certified as a drone pilot by the FAA, but was reluctant to advertise what I had done. The problem is: I don’t like drones. More exactly, I don’t like a lot of drone pilots, who think they can buzz around and bother everyone else just cause they can. Seriously, anti-drone restrictions by governments are becoming a problem, but they’re brought on by stupid, entitled behavior by some drone pilots. So not wanting to acquire guilt by association, when I began to post drone images on Facebook during the year, I claimed that I had attached some balloons to a folding lawn chair and sailed into the sky with my camera. I thought it was a clever, if albeit an obvious ruse, but there were a few who proved fairly gullible, asking me how big the balloons were and what gas I used in them. I became pretty good at sounding like I really knew how to pilot a lawn chair.

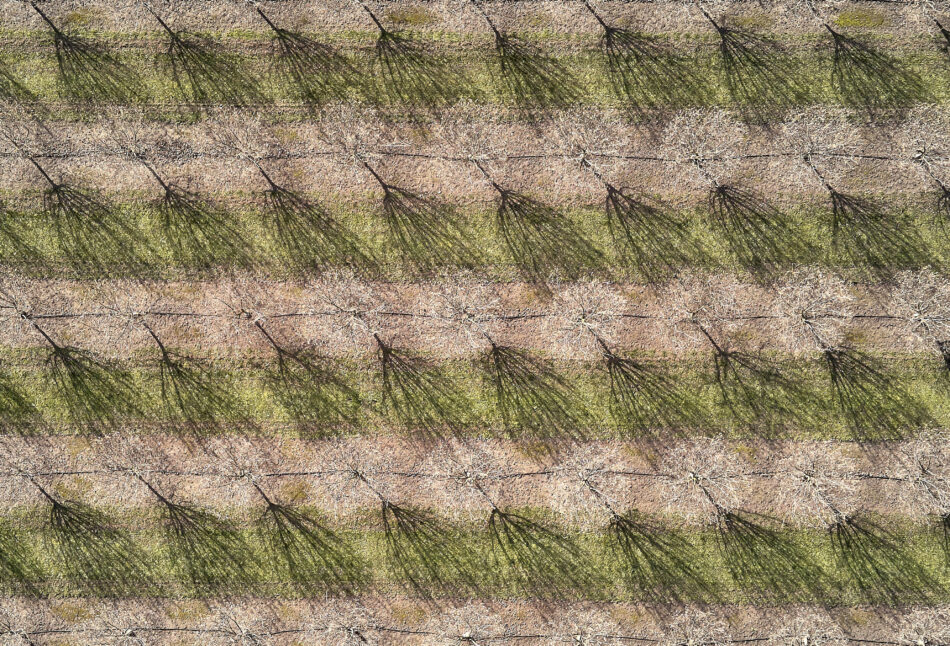

As I experimented and learned how to operate it, I was intrigued by how things look different from above, how patterns and shapes appeared from a different perspective. Circles, for example, could be found many places, including in the cooling tower of an abandoned nuclear reactor, an old railroad turntable, the waste lagoon of a paper mill, and a sewage treatment plant.

Patterns pleased me as I sailed high above in my lawn chair, including those of shadows in a hazelnut orchard and tracks in a farmer’s field.

Coastal lighthouses look slightly different when you elevate your perspective a bit. As does the Maersk Singapore when seen in Puget Sound from above. And an auto wrecking yard was a delight to gaze at from on high.

The drone is a new tool in my camera bag, and I look forward to using it in work situations. Unfortunately, on the one trip I took abroad this year, to South Sudan, I had to submit an equipment list to the government there ahead of time. I included the drone, which produced a warning from their state security officials that I was not allowed to bring it into the country. That’s a common prohibition these days, especially in countries at war. Too bad, because it would be invaluable in covering places like refugee camps.

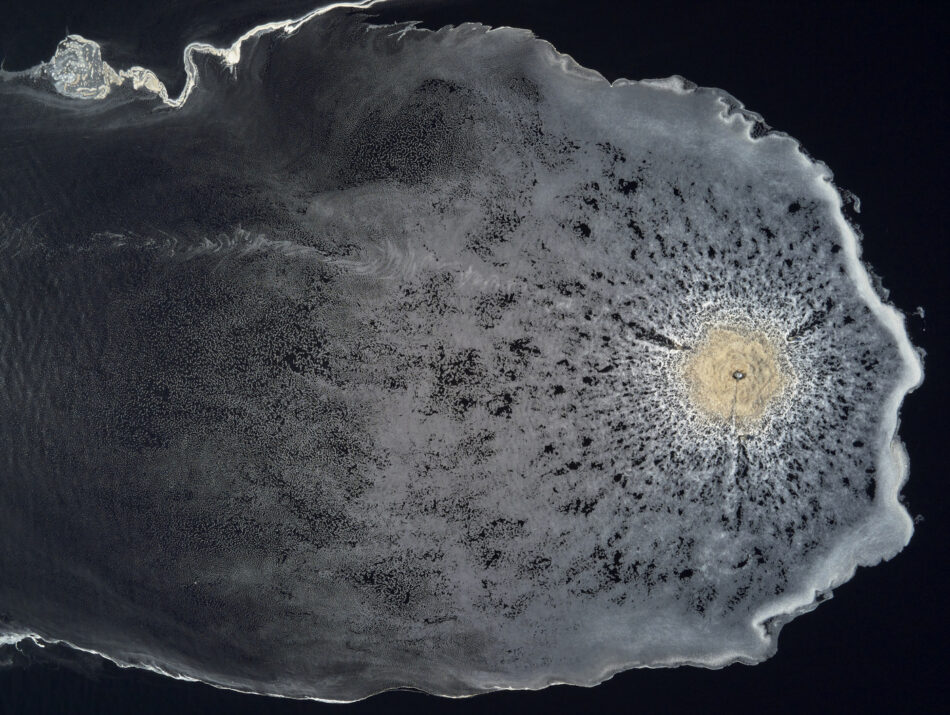

Mostly I have used the drone just for still photos, but did experiment a bit with video, again looking for some unique perspective. Here’s an example: the courtship rituals of harbor seals on the Oregon coast. For the record, lest I be confused with bothersome drone idiots, I should note that the federal government is currently developing guidelines for observing marine mammals from the air, but existing law makes it a federal crime to harass these and other marine creatures. I was over 150 feet above the water. I used a zoom to capture the action in 4K, then cropped the video in post to make the animals seem closer. I don’t believe they were aware of my presence, quietly hanging there in my lawn chair under the balloons.

By summer, I’d been vaxxed and international travel loosened up for awhile. So my colleague Sean Hawkey and I took off for South Sudan in August and spent seven weeks there, documenting the work of several church-related groups providing relief assistance, economic development, education, health care and pastoral services around the country. It was a busy time, bopping around on airplanes and helicopters either managed by the United Nations or chartered for our use. Sean, who’s from the UK, did mostly video while I shot stills but also helped with video interviews. And I’ve done some writing. The breadth of the work was immense, and there’s not enough room here to cover it. But let me offer a few visual snapshots.

South Sudan is a country at war, and we found children in Nakubuse praying for peace during a nighttime prayer vigil around a bonfire. And we found Mike Bassano, a Maryknoll priest from the United States, living inside a UN base in Malakal alongside tens of thousands of people displaced by ethnic violence.

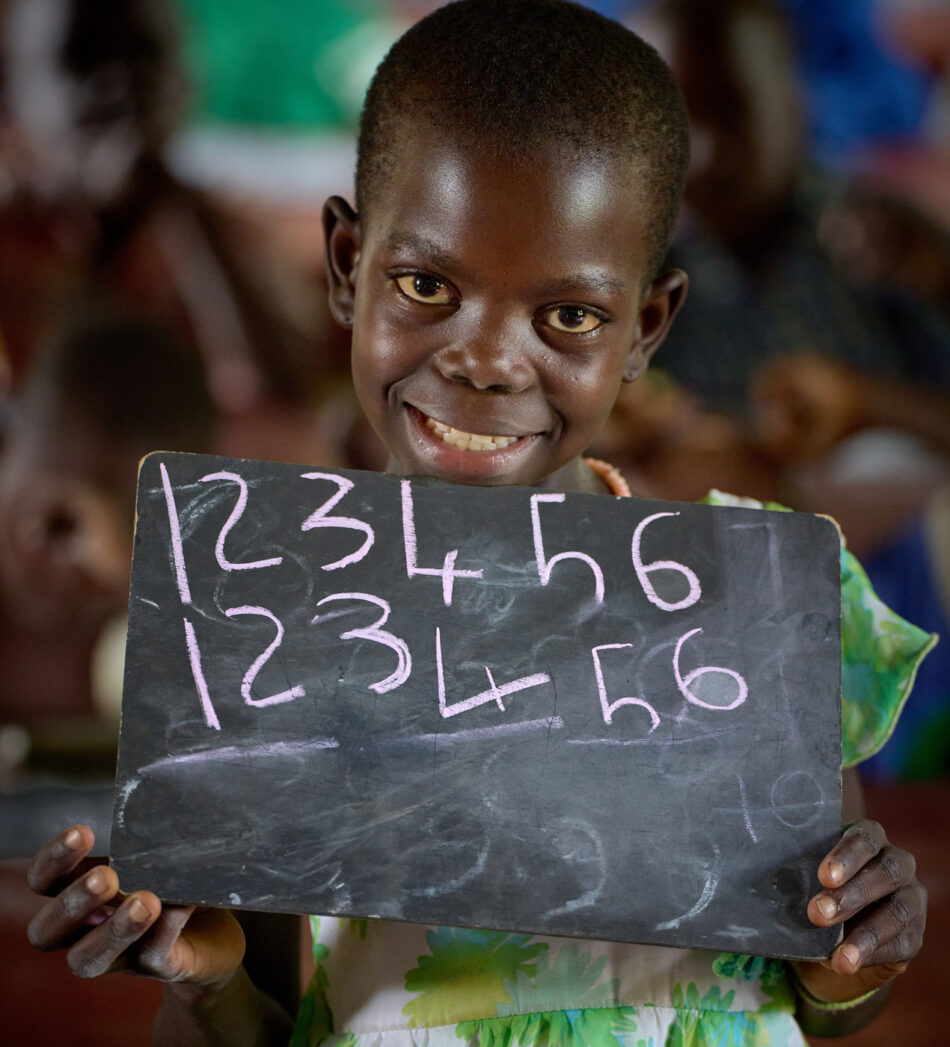

We covered education in several forms, from the training of midwives, like Regina Bangireago (in the red scrubs) learning how to be a midwife in Wau, to 6-year old Mary Saburu learning how to write her numbers in Riimenze.

We covered courageous women making a new future, from women building roads in Kuron to Mary Aping Ghor learning to read and write in an adult literacy class in Rumbek.

We looked at cattle culture, documenting the lives of people like this girl caring for her cows as smoke from smoldering dung fires swirls about her in Mogok, a rebel-held village. She burns cow dung to keep flies and other insects from bothering the animals. In the same village, a cattle keeper holds an assault rifle. Cattle raiding between neighboring tribes has long been a tradition in South Sudan, but the acquisition of high-powered weapons in recent years has turned the practice into a blood sport, and politicians and warlords have enlisted the armed cattle keepers as allies in acquiring and maintaining territory.

I took lots of photos of kids, whether they were running to school in Rumbek, holding a goat in Mogok, or suffering from malaria in Wau. And then there’s an image of a Toposa girl protecting her family’s sorghum crop in Eastern Equatoria State. She’s standing on an elevated platform where she can survey the entire field. When birds come to eat the grain, she forms a ball of mud around the end of a long flexible stick, which she then swings and cracks like a whip, sending the mud flying toward the birds. As the harvest approaches, every field has at least one such elevated platform, and children are the main protectors of the crop. Which means they’re not in school.

I photographed workshops on trauma healing, strong women with great necklaces, and men smearing their faces with ash before dancing.

And, of course, birds. Even in unlikely places. This weaver bird is working on his nest inside the United Nations base in Malakal, in the middle of a camp of 35,000 displaced people.

After getting back to Oregon in October, I trekked out to Lower Lake Creek to photograph Coho salmon jumping up waterfalls as they migrated upstream.

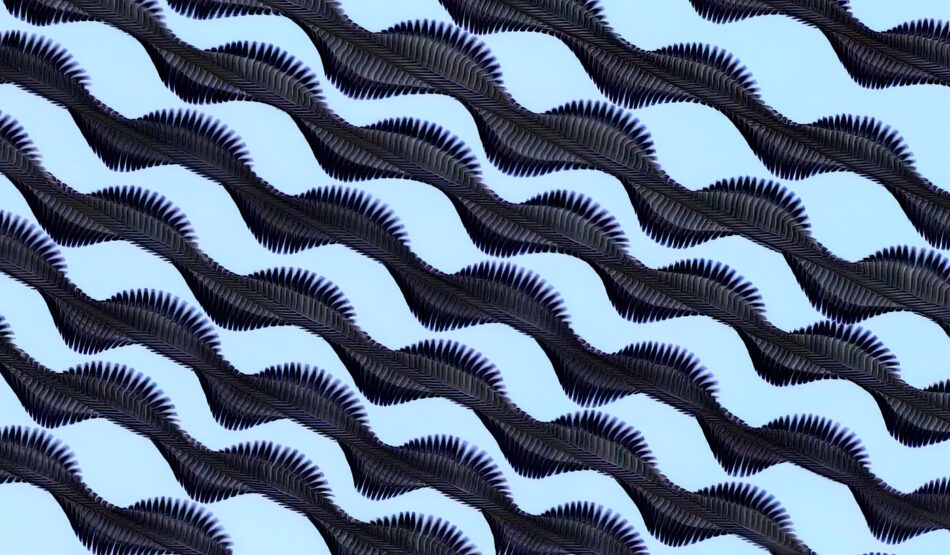

Finally, at the end of the year, inspired by the Spanish photographer Xavi Bou, I started experimenting with ways to capture the trajectories of birds in flight. Using high-speed video and then taking the individual frames of that video and stacking them to show progression, the idea isn’t to photograph birds per se, but rather to capture in a single frame the shapes that birds generate when flying, thus making visible the invisible. Here’s a formation of snow geese flying over Fir Island in Puget Sound. It’s a concept that intrigues me, and which I hope to explore more in the coming year.

This site is having trouble displaying the below comments on a browser. They show up if you access the page on a mobile device. The management apologizes for the problem, which we’re working on.

13 Responses to A Year in Pictures – 2021