Global Lens Reflections on life, the universe, and everything

A Year in Pictures – 2025

After decades of traveling afar to photograph the world, I’m discovering in semi-retirement the joy of capturing images closer to home, whether it’s an Anna’s hummingbird slurping nectar in my back yard from a native honeysuckle covered with honeysuckle aphids, or my 3-year-old grandson blasting through a puddle in my front yard, or thousands of my friends and neighbors marching in a pro-democracy demonstration just a couple of miles down the street.

In April I celebrated the annual return of Cedar waxwings (Bombycilla cedrorum)–one of the most beautiful birds around–to an Osoberry bush (Oemleria cerasiformis) in my backyard. They love to play with their food.

And in the fall the Pacific tree frogs (Pseudacris regilla) become guardians of the grapes. Actually, they sit there when the grapes are ripe and wait for an unsuspecting bee or fly to land in search of grape juice.

In the fall our Showy milkweed (Asclepias speciosa) puts on a chaotic show about the same time as the nasty Dogwood sawfly (Macremphytus tarsatus) takes up residence on a Red-osier dogwood in my back yard. It migrated to our region from the east coast and is widely considered a pest.

Twice a year the Vaux’s swifts (Chaetura vauxi) pass through. In the spring on their way north, and in the fall on their way south. Since we’ve cut down most of the old trees they used to use as temporary lodging, they’ve learned to use chimneys, including one on the nearby University of Oregon campus. Here they are plunging into the chimney at dusk. (I employed a technique that takes individual frames of high-speed video and stacks them together into single images that illustrate movement.)

Another sign of the changing seasons is the migration of Coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) up the streams that carve up the coast range west of us. Here’s one jumping up nearby Lower Lake Creek falls in early November.

And even when I leave home, I can’t help but watch for birds, whether it’s a male Pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus) on Whidbey Island, or a Cinnamon hummingbird (Amazilia rutila) and a Scarlet macaw (Ara macao) in western Honduras.

And Crisanto Méndez Jiménez reminds us that people can fly as well. He plays a flute and drum as he and three other voladores (flyers) descend to the earth in Chapala, Mexico. They are heirs of a tradition that originated with the Totonacs, who lived near Papantla in what is today the state of Veracruz. Spinning to earth around a tall pole, they enact a sacred ceremony begun some 450 years ago to convince the sun to end a drought by letting it rain.

In Tanzania in November, all I had to do to see wildlife was look out the window of the priest’s home where I was staying in Mwanza in order to watch a Vervet monkey (Chlorocebus pygerythrus) chow down on a piece of fruit.

For the second year in a row, Lyda and I traveled to a remote corner of Alaska tucked into northern British Columbia where Brown bears (Ursus actos, also known as grizzlies) chase after spawning salmon in the Tongass National Forest.

When there were no hungry bears hanging out, the beavers kept us entertained.

Traveling the islands of British Columbia involves a lot of ferry trips, like this one from Moresby Island to Graham Island in Haida Gwaii, where we spent several nights enjoying the quiet of remote First Nations communities.

When we camped above the Salmon Glacier high in the mountains of B.C., Lyda always seemed to get the picture window, yet inexplicably slept in rather than oohing and awing the scenery. When she finally did wake up, she said it was cold and argued for returning to sea level.

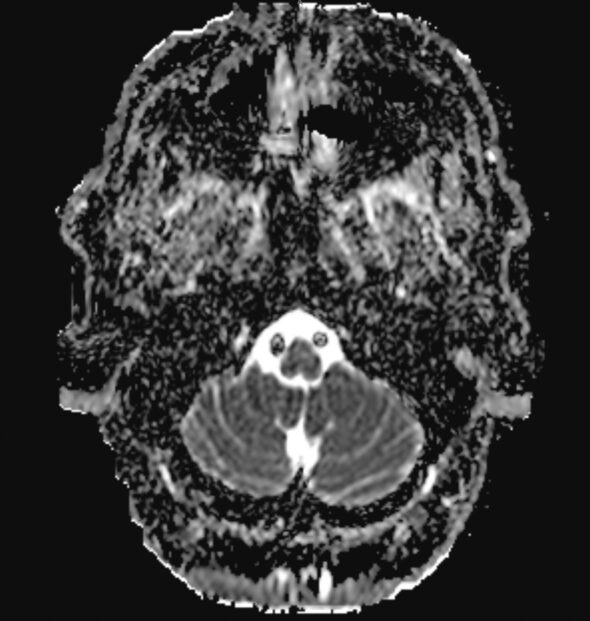

I’ve decided to keep Lyda a bit longer. Age is catching up with me, and I need someone to take care of me as my body disassembles. During 2025 I had several MRIs in an attempt to track down some recurrent dizziness. Fortunately, they found nothing serious, though the presence of a weird looking duck in the middle of my brain did raise some eyebrows.

I did accept a few assignments in 2025. In Minnesota, I captured Sherril Brown standing proudly in her apartment in Restoring Waters, a housing project in St. Paul for women and others who are homeless and also wrestle with mental health or substance abuse challenges. Restoring Waters is part of Emma Norton Services, long supported by United Women in Faith.

In Honduras, I photographed Jesuit Father Carlos Orellana preaching during Mass in the San Isidro Labrador Catholic Church in Tocoa. Behind him is a portrait of Juan López, a Catholic delegate of the word who was assassinated in Tocoa in 2024. I went to Honduras to write about the aftermath of López’ death. Orellana blamed the town’s mayor for the killing, one of a series of murders of church workers and environmental activists who’ve been martyred in recent years for defending the poor and the environment in a narco-state run by drug kingpins like former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernandez, who trafficked 400 tons of cocaine into the U.S. but was pardoned by Trump, thus strengthening the grip of the cartels on daily life.

I also wanted to write about migrants being deported to Honduras by the Trump administration, so I spent time with Scalabrinian Sister Idalina Bordignon. A native of Brazil, she directs a church-run reception center at the international airport in San Pedro Sula. Here she is welcoming a planeload of deportees in March.

Accompanied by his mother, Alicia Rodriguez, Alex Ramon Dubon leaves Bordignon’s center. He was deported from the U.S., where he lived for the last seven years, after being detained while working on a construction site in Louisiana. His wife and three children remain in the U.S. Rodriguez traveled several hours to the airport to greet her son.

One of the more unusual stories I’ve worked on in recent years was a picture–heavy article about Sister Alegria (right) and Sister Confianza, members of the Amigas del Señor (Women Friends of the Lord) Monastery in Limón, Honduras. Here they are praying during evening compline. They moved from their remote monastery to a house in the seaside village because of Sister Alegria’s illness, which confines her to a bed. Originally from the United States, the women founded the monastery in 2006.

The women take seriously the challenge of voluntary poverty. So Sister Confianza scavenges in the village’s landfill, looking for a reparable chair. They are firm believers in reuse, repair, and recycling, and find many of the household items they need in the local dump.

Late in the year, I worked on several stories in east Africa, including one looking at the immediate effects of the Trump administration’s demolition of USAID and other funding for AIDS programs in the region, where a key to reducing new HIV infections has been stopping the transmission of the virus from mother to child. When women have access to anti-retroviral drugs, their viral load can be suppressed to the point that the virus won’t be passed on to their newborn children.

In this image, nurse Nancy Mwai is taking blood from the finger of Eliana, a six-week old baby girl, in a clinic in Mathare, a slum area of Nairobi. She’s going to test the blood sample for HIV. Her mother has been HIV-positive for three years, but has faithfully taken her meds and earlier gave birth to a child who is HIV negative. She’s confident that Eliana will be as well.

The clinic is sponsored by a program that’s been hard hit by the Trump attack on public health. Although Kenyan AIDS programs were moving steadily toward self-sufficiency in 2030, the abrupt end to U.S. support in 2025 meant the program had to lay off more than half of its 400 workers and close eight of 14 clinics.

What’s particularly troubling is that the program had a success rate of more than 98 percent in preventing mother-to-child transmission of the virus. Part of that success is due to the use of community health care workers and peer mentors, volunteers who visit the clinic’s clients in their homes, accompanying them on their journey to wellness. Women like Florence Mwikani, a Catholic who volunteered 33 years ago to be a community health care worker, even though in those days that mostly meant accompanying people as they died. She received a $20 a month stipend for her work, but that ended in October. She continues to work without pay, telling me her ministry is a calling, an opportunity to act like Christ toward her neighbors. Yet she worries about what will happen to her neighbors when there’s no more money for life-saving antiretroviral medications. That’s a widespread worry in the region.

Working on a related story in neighboring Tanzania, I got to know Laurencia Makanya, who sells vegetables and charcoal from a small stall in front of her home in the village of Tx, just outside Mwanza. She participates in a savings group coordinated by a church-sponsored group supporting and empowering people living with HIV. She currently buys the vegetables at the market to resell to her neighbors, but she’s saving money with the hope of purchasing a small plot of land to grow her own vegetables.

In Igombe, I photographed children in a church-sponsored school.

And I documented the work of Maryknoll lay missioners like Loyce Veryser, a math and science teacher at a resource-challenged school in Mwanza.

I documented life in Mwanza’s Mabatini neighborhood, where women pray during Mass in the St. Jude Thaddeus church.

The priest of that parish is Maryknoll Father John Siyumbu, a Kenyan who I spent a couple of days shadowing. He’s obviously loved in his parish, though these woman who were styling hair under a tree had ambitious ideas for what they could do if he let his hair grow longer.

To research a story about how Maryknoll trains its prospective priests, I spent a couple of days hanging out with some in Nairobi, including Norbert Jeremiah, whose pastoral practice includes accompanying homeless families in the Mathare slums, and Alois Simpilisi, who here chats with a young patient during his chaplaincy work in the St. Francis Community Hospital.

I photographed girls studying for an exam at the Kebaroti Mixed Secondary School in Migori, in the southwest of Kenya. With support from Maryknoll, the school is constructing a dormitory for 200 girls, allowing them to stay at the school, thus reducing adolescent pregnancies and helping to keep girls in school.

Nearby, Eunice Mariba Rawi shells beans she has harvested with her son Kevin in Gwitembe. It’s a region that’s been hard hit by ethnic conflict and the climate crisis. The woman’s husband was killed three years ago during the conflict, and her family has lost most of its farmland. She hires herself out as a laborer to other farmers in the area in order to buy a small amount of food, but she also receives critical food support from Maryknoll.

In Kavete, on the other side of Kenya, Regina Mumbua uses a donkey to carry water home from a community water point at Christ the King Catholic Church, where Maryknoll financed a well and storage system that provides water to a community hard hit by the climate crisis. Another woman carries water home on her head.

I’ve written extensively about glue-sniffing in Latin America. It’s also a huge problem in Africa, as experienced by this man in Nairobi.

As the pro-democracy movement has grown in the first year of the Trump administration, I photographed protests and marches in Eugene and nearby cities. Here’s an image of mine from an April demonstration in Salem, for example, that was used in several European newspapers.

The numbers of people turning out has been impressive. Here’s a March protest in Eugene.

While many protests were generated by generic opposition to Trump’s assaults on decency and democracy, some had a particular focus. Here’s Neil Penn, a Jewish peace activist, speaking at an October rally in Eugene in support of peace in Gaza.

Here are images from a June protest in Eugene against war on Iran and a December protest in Eugene against war on Venezuela. (The NO people were the first part of a giant “NO WAR!” message in front of the federal building.)

Despite Trump’s claims that they were all thugs employed by George Soros, I was repeatedly struck by the positive energy from so many ordinary people.

Activists have kept up a regular vigil in front of the ICE office in Eugene, and when a woman was unjustly kidnapped by ICE in Cottage Grove, community members turned out for a candlelight vigil in solidarity.

The war on Gaza in particular took center stage in many passionate protests. Here a man speaks during an August town hall by U.S. Congresswoman Val Hoyle (D-Oregon) in Eugene. A number of people present took issue with Hoyle’s position on the U.S.-supported genocide in Gaza.

Thousands of people can come together in common cause, but each brings their unique perspective.

During a No Kings demonstration in Eugene, here’s a woman carrying the burial flag of her father, who fought fascists during World War II.

In some places, faith groups have taken the lead in combating racism and violence. In this image, Louie Llenado raises her fist and shouts as United Methodists demonstrate in solidarity with their neighbors being held in the Northwest ICE Processing Center in Tacoma. During the September demonstration, participants prayed and sang, celebrated communion, listened to descriptions of life inside the for-profit prison, and chanted “No estan solos! You are not alone!” and “Free them all!” as buses brought in newly detained persons.

Bishop Cedrick Bridgeforth led participants in celebrating communion. Among those assisting was Lyda, on the left.

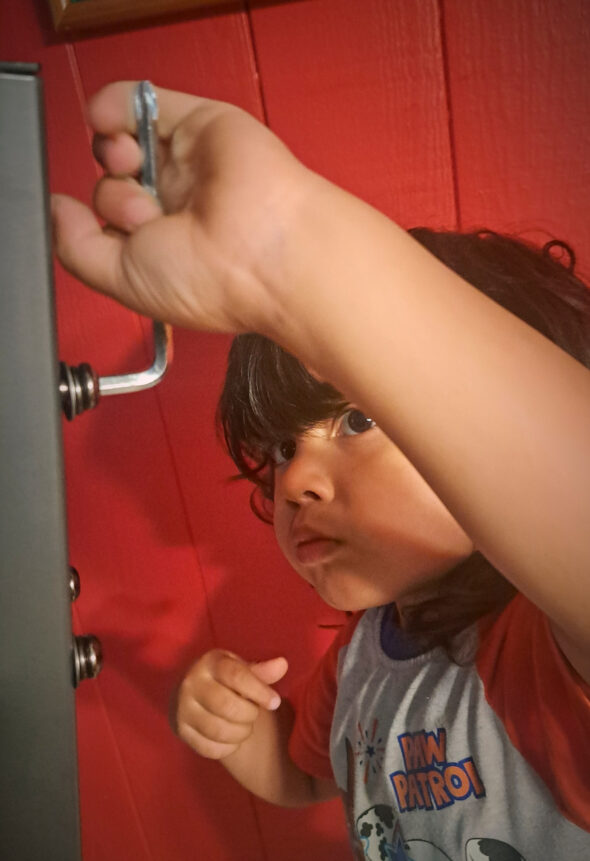

We’ve taken our grandson, known to many as The Little Guy, to a few protests. You can’t start his education too early. But he is rather easily distracted.

Speaking of The Little Guy, he turned three early in 2025.

He spends a lot of time with Lyda and me, learning everything from proper hygiene, how to make s’mores, the need to take apart everything in the house (reassembly is frustratingly optional), the importance of proper shaving, how to dance with your shadow, and how to build a sandcastle.

We have the privilege of accompanying him on adventures ranging from going to the eye doctor to taking his first train ride.

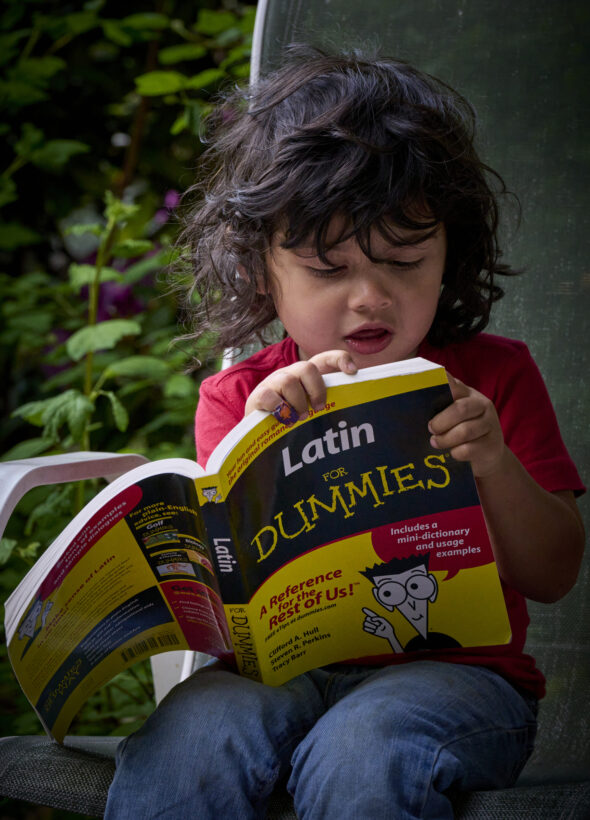

After the death of Pope Francis, there was a groundswell of support for The Little Guy’s election as Pope, so he hit the books to properly prepare. Inside sources tell me he narrowly lost to the guy who became Leo.

At another point he formed his first boy band, and commissioned an album cover showing him standing heroically atop a garbage bin.

He loves to get pushed around by his cousin, The Other Grandchild. (She doesn’t live in Eugene so we sadly don’t see her as much.)

On Halloween, when we went to public celebration downtown, he ran around excitedly throwing webs onto complete strangers.

The Little Guy loves crabs, his bicycle, and looking cool.

But highest among his preferred activities is hanging with Nana, whether it’s to read a book or play bumper bins.

As The Little Guy grows older, we’re fascinated and blessed by his growing grasp of our complex world. What a privilege to accompany him as he grows in stature and wisdom.

One Response to A Year in Pictures – 2025